I have not found that book learning and on-the-job-training gave me the tools I needed to understand and help people. Instead I have had to use experience, curiosity, and following my own spirit or moral compass. Now, I think this is largely because I didn’t understand the realities of black market America with compassion. Without understanding the rules, the pros the cons and the oppression that results from the crime industry it can be hard to provide the necessary empathy and validation to establish connection and be supportive. Because I didn’t get that training in school, I have had to undergo a journey to learn to be helpful.

As I have come to see it, in poorer communities the impact of black market America functions as an iron curtain that some earnest people who enter the field are not formally trained to understand or believe. It’s true that social workers who come from these communities may recognize black market realities quicker than I have. Indeed, I can recall co-workers who really helped me understand things along the way. On the other hand, perhaps it just takes a lot of time to understand streets and crime well enough to see how it shows up in peoples’ behavior and the decisions they make. Indeed, navigating this world in poverty and without financial aid is not an easy thing to do.

Still, many social workers like me stay encapsulated in their world view for extended periods of time. While some of us are only there to do our training in poor communities, many of us stay in them with our salaries and the discourse of our profession, things that keep many of us insulated.

What School Didn’t Teach Me:

In school, I took sociology and counseling psychology. I learned a lot about injustice in third world countries and wealth-fare (tax breaks for the rich,) but this did not prepare me to understand the affects of corruption and crime on our society’s most vulnerable individuals, the homeless, protective custody parolees, and the people with mental health challenges like addiction and schizophrenia.

I have generally been considered a conscientious social worker performing high in stats and looking good on paper. But learning how to get street smart and overcome the limits of my own world view has taken upper-middle class me a long time. I have come to believe that crime is a legitimate industry in this country that is vital to redistributing the wealth. It plays a bigger part in governing vulnerable individuals than social workers who do not understand it can. And yet vulnerable people are often victimized by its machine and need to express themselves and need support to help them find the freedom they may seek.

On the Ground Lessons in Black Market America:

About six years into my career, I moved and took a job in a Seattle, Section 8 Housing Authority Complex. It was a position that no one else would take. I did so brashly. When I found out my boss who I had witnessed expel a naive client who was unwittingly letting a boyfriend deal drugs out of her apartment, had a drug problem herself, I stopped heeding her.

The needle and pipe drug trades were visible throughout the housing complex just by taking a flight of stairs. The management had records on their residents that were off limits to us. I didn’t really understand that my desire to help the poor mentally disturbed individuals instead of the dealers and thugs made me a liability to the powers that be who hired me.

I didn’t disapprove of the residents who became addicts. However, as I started to see that the focus of the authority management, the police and the power brokers were not utilizing their resources on safety, I started to become protective. I didn’t initially realize that by disapproving of the violence and corruption that come with the drug trades, that I was essentially putting myself at odds with the powers that be. I was becoming a vigilante.

Who Was I and Why Was I in this Situation?

Back in college, I had taken up residence in the ghetto community that surrounded the commuter university I attended. I had caught a case of male anorexia in the private prep school I attended and wanted to evade the people who tormented me, like my parents who were on the faculty. I worked and studied and was so isolated to have not attended a single college party.

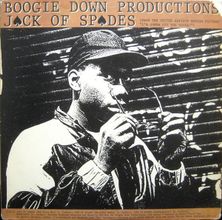

I secretly believed that the suburban social working professionals that I interviewed for school projects were burned out cogs in a machine. These social workers I interviewed didn’t seem to understand or help the people I worked beside in the local businesses that paid under-the-table wages. I believed, I’d learned more from a three-minute KRS-One lecture blaring out of the radio in the deli I worked for, than I did from those interviews.

But money was tight, I needed a job, and I was after all a high performing student with a stellar work ethic. When my isolated life style resulted in a second mental health crisis, the therapist I found was always directing me to go on social security. I found myself locked up for a month and started on a high level of medication cocktails that catapulted me over the barrier I was facing. Finally, I accepted a role as a social worker.

Instead, of social security, I got a master’s level job and started a master’s program. I did eventually excel on the job, graduated and got promoted to the highest level before going into management. I knew how to work with people and had satisfied customers. Still, I used significant clinical barrier between the people I worked with and my own state of mental health. I really did not relate to them or use my lived experience to be helpful.

Learning My Lesson:

Back at the section 8 authority compound, one resident, who had proved to be an accurate intelligence source, told me that he admired my ways, but had heard word that I might become a resident myself one day and he feared that for me.

Now, the story is very complicated, but when I did face specific personal threats and fled for the Canadian border, the police did stop, separate me from my car and track me until I was admitted for three months into a state hospital in Montana.

Before I could get back into social work, I had to accept an arranged job at a suburban Italian Delicatessen. Coming out of a period of transience, I had to accept that my belongings were moved around in the apartment I could barely afford. I had to accept that my employment related mail was opened before I could get to it. I had to accept that I frequently ran into street people who suggested they worked for the CIA. And finally, I had to accept that I had to bike twenty miles a day to get to work and back. Finally, I went on medication and admitted that I was a schizophrenic. Not until I was able to make friends with the workers and bosses at the Italian Deli did I find myself granted the opportunity to go back to social work.

Lessons Learned:

What I have learned about being a social worker is that it is important to respect the crime industry and the limits of my own power. Within the section 8 complex there were likely informants and spies who were cutting deals ultimately to save lives even though lives were lost. Keeping the money flowing including that of my low wage pay check is always part of the game.

At one point, the newspaper reporter I was speaking to wanted to go undercover in the building. She did not understand that the whole power structure knew who she was and expressed anger at me for speaking to her before she even left the building.

One could argue that social workers do work for the system and are not paid to start social movements. When I was in college and judged the system in a negative light that kind of statement would have been very discouraging to me. But I have found that the social worker who is committed can understand all the mechanisms of injustice and go as far as they can to stretch against the seemingly stagnant system they work for and help their individual clients find the freedom that they seek.

I got a lot of help from reading books like Patrick McDonald’s Memoir on growing up in South Boston, All Souls Day. I found this book taught me a lot about how gangsterism affects impoverished families.

Social workers should not, in my opinion, take their privilege lightly. They should not presume that they could handle the lives their subjects are suffering through. Finding freedom often involves a die-hard belief in the impoverished citizen’s ability to find a role they feel passionately about.

I would not take back anything that happened to me. Social work is still good work. Don’t ever give up your sense of justice that brought you to it in the first place. But remember that people always have a right to move their lives in a healthier direction.

Patrick McDonald, All Souls Day: A Family Story from Southie, Beacon Press, 2007

Many thanks, this website is extremely beneficial.|