Never saw my hometown until I stayed away too long

I never heard the melody until I needed the song . . .

. . . I never I spoke “I love you” till I cursed you in vain

Never felt my heart strings until I nearly went insane

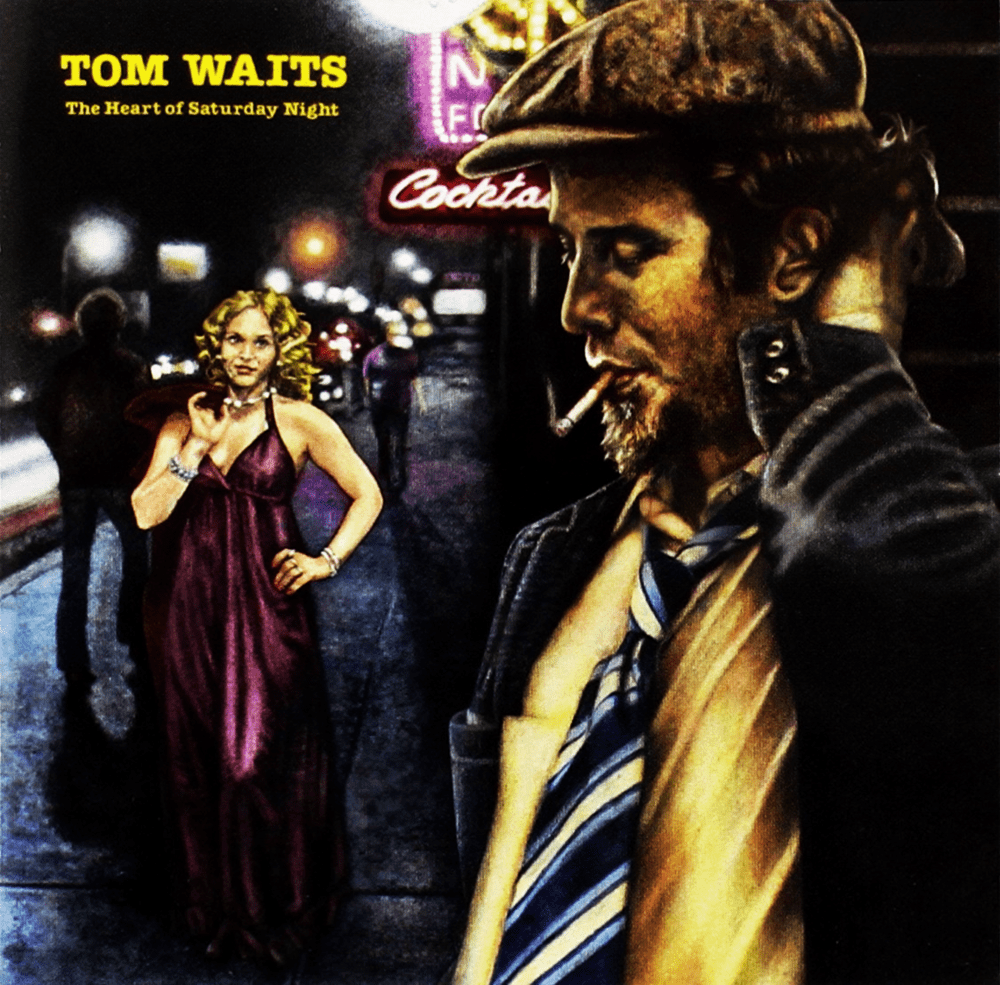

–Tom Waites, San Diego Serenade

It is funny how sometimes one cannot really see themselves until they get a glimpse of a harsh paradoxical reality. Perhaps doing so gives one that alternate perspective that is so necessary to really see oneself and gain wisdom. I think that’s what Tom Waites is getting at in the excerpts of his song I posted above. That is why the ability to relate to others is such a powerful teacher and healer that is so needed in a therapeutic endeavor. Other people’s struggles help us stop and see ourselves better. Even if it is painful, growth is likely.

And, just as the song goes, I never really saw myself as a learning-disabled person until I just recently had the opportunity to sit with an individual while she was receiving a mid-life diagnosis. It was a diagnosis that I thought might be helpful. Little did I know that before this sitting, I rarely considered the full effect of how a learning disorder affects me as a writer, therapist and mental health consumer.

***

Learning disorders, as I often educate people as a psychotherapist, are an aspect of neurodiversity that are most characterized by an imbalance in areas of brain abilities. Some realms may be significantly lower, while other areas are particularly high. Thus, as my explanation goes, certain areas of learning become very difficult without a high level of support, time and determination. A person who struggles in this manner may suffer from attention difficulties, may need extra time to complete things, and may like Albert Einstein, develop a particularly high drive to exercise their strengths because of always struggling and straining to keep up. Of course, when not properly supported and safely nurtured learning disabilities can cause people stop exercising abilities and accept oppression.

I am also likely to talk about how learning disabilities are generally considered to be neurodevelopmental disorders. This means that they are severely impacted by a mix of biological and environmental stressors. There are a couple of points I accordingly am likely to highlight.

First, I will suggest that we are learning, intergenerational trauma can be inherited and this might contribute to the brain’s lower abilities. Second, I will argue that having learning struggles can lead to a resulting life of ongoing trauma and mistreatment that can add to and exacerbate the lower realms particularly if support is not provided. Thirdly, I will point out that it is well known and demonstrated that trauma results in brain damage and that learning disabilities give us an opportunity to address those issues of trauma. And most certainly, I will add that compensating for a relative deficit may cause there to be unusually high ability in some other areas and exercise always makes them stronger.

In addition, after making these points, I am certain to reference studies on resilience that demonstrate that healing from trauma and neuroplasticity can cause people to become stronger than they would have otherwise been. In fact, being damaged can cause the brain to strengthen up in ways that would not otherwise happen. Thus, creating a sense of safety and providing people the opportunity to heal from trauma enables them to grow so strong that they become grateful that the trauma happened. Many who attain that sense of safety become very practiced at being strong, spiritual, and high functioning individuals.

***

Unfortunately, the African American woman I referred for testing got informed that she had learning disabilities, without having any of my suggestions reinforced. I found myself reflecting on the fact that maybe my ideas are simplistic and not scientific. Instead, from my perspective, the focus was on what she couldn’t do, and what was possible to help her overcome these deficits thanks to modern technology.

I went home after the sitting, was editing a chapter of my current book, and suddenly found myself so hypercritical that I froze. It occurred to me that I don’t read the way others do. In fact, I hate reading so badly that I rarely look extensively at the work of others. Everybody says that to be a good writer, one must be a prolific reader. I usually tell myself that I learn through writing, not reading. I usually say that I am exercising my talents, making myself happy, and learning rather than wasting my time.

But in a frozen state, it occurred to me that I am not being realistic as so many negative people in my life have told me. Maybe those fears I am constantly working against really are true.

All the rejections I have been getting from journals and blog sites plus the people who have used the vulnerability in my work to politically marginalize me started to gain tractions in my head. Frozen, my sense of empowerment felt like it was swallowed up and wallowing in stomach acid. The fact that I won five literary awards for my memoir didn’t matter. Instead, I found myself returning to perseverations on the ways that my memoir has only heightened my sense of alienation. All that mattered was that it was not selling, attracting reviews, or achieving what I had hoped for, to decrease my sense of invisibility. Suddenly, instead of being unrelenting and meticulous during my seven-year struggle to write the thing, I told myself that couldn’t read the way other people do and that my writing must show it. I told myself that I had to work twice as hard as others to no avail. Old tapes started to dominate the day.

“You wouldn’t believe it,” one writing professor had complained in a college course, “but it took me ten rewrites to get my detective novel published!”

“Ten rewrites,” I had once been proud to say to myself, “that is nothing! And I am having fun.”

Suddenly, that confidence that once helped me thrive was taken away.

***

Sure, in school, I was always the last person to complete the test, but my grades were always good. It’s true some teachers tended to get on me about spelling that I could not do anything about, but I tested okay in meaningless math. It’s true when the homework got heavy in high school, I could only manage to get four hours sleep a night, but that was also because I played sports, exercised, and didn’t eat much. When I became addicted to starving, I just thought I was a hardworking perfectionist who didn’t want to be stopped.

When anorexia led to incarceration, I was forced to halt all behavior and gorge on food. Once the tears and fight subsided, I learned to write when I couldn’t exercise.

It’s true I had poured my heart into my poetry notebook the year before only to receive a B+. The comment from the teacher to my mother—the school reading teacher—was that my work was just too depressing. She didn’t like it.

Straight out of the hospital and still angry about the B+, I took writing assignments and turned in lengthy stories or songs instead. I wrote twenty-five-page papers with long bibliographies. The results: poorer grades and a college essay nearly got me kicked out of school because it made the school psychologist—my teacher’s wife and mother’s friend—think I was suicidal. I still wasn’t educated enough about the social psychology of the situation: I was exposed as a mental health patient, my grades suffered regardless of how good I was getting. I had a different experience and message than others. My successes, leadership, and hard work in eleventh grade became a subverted, living lie. When I chose my only available form of rebellion against this, to go to a local commuter college, the school chose to lie in the yearbook and said I was going to overpriced Antioch College in Ohio.

I ran as far away as I could run without using the college money which I suspected had gone to hospitalizations. In a ghetto with a girlfriend who was seven years my senior, it was the easy courses with lousy textbooks that got my GPA off to bad B+ start. Suddenly immersed in large crowded auditoriums, my anxiety went up and my attention, down. I would be struck with the worst kind of writer’s block. I started the practice of outlining and memorizing everything that I read. I ended up achieving a 3.9 average, but I never went to a single party or took any time off work.

My poetry teacher in college who repeatedly chose my poems to share with the class had once said at the end of an intense semester in which we wrote a poem a week: “Then, there will be some of you that have to keep on writing, not because you want to, but because you have to.”

I don’t know if I listened to him or if I just found myself to be one of those who had to write. I took fiction and personal essay classes and obsessed over my take-home exams trying to get the wording just right.

I did get diagnosed with learning disabilities working my way through graduate school. Because I was working with a psychologist who unbeknownst to me didn’t think I was college material, I became very aware of all my deficits and tended to communicate about this with my peers. I took a heavy dose of medications that I later found out I didn’t need to such an extent. Interactive courses in which the info came from multiple sources and required in the moment listening often overwhelmed me. I put my writing away during those seventy-hour weeks and did my best to become involved and social with my peers. I learned that I worked oh so much harder than they did to prepare for tests. I often got ridiculed for asking so many questions to keep myself alert and tracking, but I was used to that. When I got through those three years without a hospitalization, I happily returned to an intense poetry habit.

***

I must admit it was my suggestion that the African American woman get tested for learning disabilities. At least I educated her about my views of learning disabilities before I set up the testing. However, I was still stunned by the outcome. I later learned that the specific tests used were known to be culturally biased against African Americans. On a closer look at the material there were in fact areas of superior performance that we neglected to review. I am using this essay to thaw the writer’s block that has struck me in the gut over the past few days.

I do believe I will return to being happy obsessive, unread writer for my own lonely needs again.

A year after I graduated, I moved to the west coast to start over again. I think of the times since: when things were hard; when I had to escape incarceration and face homelessness, underemployment and long work days just to evade the mental health system and get back on the career track. When I think of these experiences, I get mad that people are reduced to different types of pathological disorders, like learning disorders. At the same time, as soon as I developed the diagnosis of schizophrenia, learning disorders didn’t matter anymore. I became a warehoused genetic cash cow. In the mentality of mainstream treatment, schizophrenia trumps neurodevelopmental disorders, yet so many of the institutionalized individuals I work with struggle with undiagnosed and unsupported learning disorders.

They are brilliant, complex, utterly alone, living in squalor, and extremely righteous and good people. I just don’t understand why psychological tests and treatments, and the demands of society make it so hard on good people to make a living wage.

***

Perhaps, the reader can tell, I have decided to be out with my history and experiences as a professional, writer, and mental health consumer. I still find there are many people who pick up on the fact that I am a little different and try to scapegoat and marginalize me. It happens repeatedly like the rising ebb of the San Diego sea on the shore as Tom Waits at one point had pondered.

I never saw the mornin’ ‘till I stayed up all night

I never say the sunshine ‘til you turned out the light . . .

. . .I never saw the white line, ‘til I was leaving you behind

Never knew I needed you until I was caught up in a bind

Really, it still hurts because criticism comes from every direction. However, eventually the hurt will go away. I will still be writing. And I hope and pray that that brilliant person I got diagnosed with a learning disability will be there with me, making the most of her meaningful life no matter what “they” say.

You’re a really valuable website; couldn’t make it without ya!|